Your light electric vehicle suddenly loses power on a highway. Your power tools die mid-project. Your energy storage system fails during peak demand. These problems trace back to one thing: misunderstanding how lithium-ion batteries actually work.

Lithium ion batteries power modern electronics, electric vehicles, and energy storage systems by converting chemical reactions into reliable electrical energy through advanced cell chemistry, precise internal design, and optimized real-world performance.

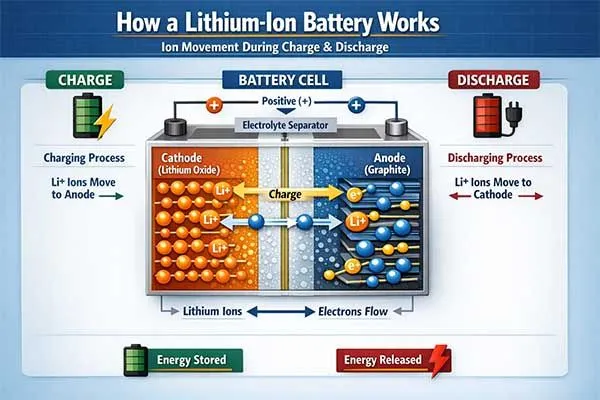

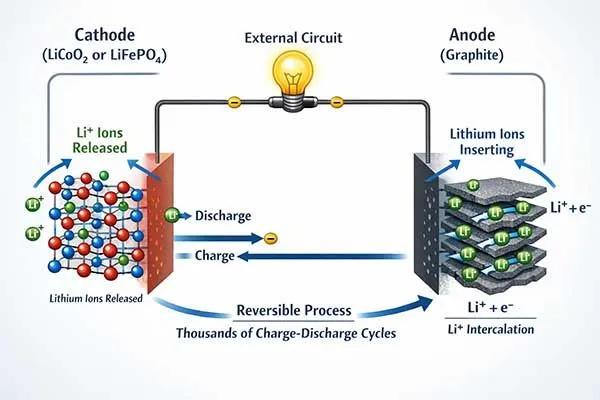

Lithium ion batteries work through reversible electrochemical reactions where lithium ions move between a cathode and anode during charge and discharge cycles.

Many lithium ion batteries manufacturers and end-users suffer losses because they don’t grasp the basic chemistry and design principles that govern battery performance.

The energy density of lithium ion batteries depends on the electrode materials, cell design, and electrolyte composition.

During discharge, lithium ions flow from the negative electrode through the electrolyte to the positive electrode, generating electrical current. This process reverses during charging, allowing the battery to store energy repeatedly.

Understanding battery chemistry helps you select the right cells for your application, avoid costly failures, and maximize performance.

Keep reading to discover the detailed mechanisms behind battery operation and what makes certain designs superior for specific uses.

Table of Contents

- What Chemical Reactions Power Lithium-Ion Batteries?

- How Does Cell Design Affect Battery Performance?

- What Factors Determine Real-World Battery Lifespan?

What Chemical Reactions Power Lithium-Ion Batteries?

The fundamental chemical reaction in a lithium ion battery involves lithium ions moving between layered electrode materials through an electrolyte solution.

At the cathode, metal oxides like lithium cobalt oxide or lithium iron phosphate release lithium ions during discharge. At the anode, typically made of graphite, these ions insert between carbon layers and combine with electrons from the external circuit.

This intercalation process is reversible, allowing thousands of charge-discharge cycles.

The chemistry behind lithium batteries involves multiple components working together. Each part plays a specific role in energy storage and delivery.

The performance you get from your battery pack depends directly on understanding these chemical processes and how they interact under different conditions.

The Cathode Chemistry and Material Selection

The cathode determines most of the battery’s voltage and energy capacity. Different cathode materials offer different trade-offs between energy density, power output, safety, and cost.

NMC (Nickel Manganese Cobalt) cathodes provide high energy density, making them ideal for electric vehicles and unmanned aerial vehicles where weight matters. LFP (Lithium Iron Phosphate) cathodes offer better thermal stability and longer cycle life, which works well for energy storage systems and recreational vehicles where safety and longevity outweigh energy density concerns.

Safety First: Managing Thermal Risks

Termal management starts at the chemistry level. Cathode stability, electrolyte composition, and separator quality directly influence thermal behavior, making material selection a critical factor in preventing overheating and thermal runaway.

At Long Sing Energy, we test both cathode types extensively in our Chinese manufacturing facility. During the sampling phase for a recent electric mobility project, we prepared NMC cylindrical cells with different nickel ratios.

The first batch showed excellent energy density but failed thermal runaway tests at 150°C. We adjusted the composition, reducing nickel content from 80% to 60%, which lowered energy density by 12% but passed all safety requirements.

After three sample iterations over six weeks, the client approved production. This process taught us that cathode chemistry selection requires balancing multiple performance factors based on real application needs.

The Anode Structure and Lithium Storage Mechanism

The anode in most lithium ion batteries uses graphite because carbon’s layered structure accommodates lithium ions efficiently.

During charging, lithium ions leave the cathode and insert between graphite layers at the anode. Each carbon layer can store one lithium ion for every six carbon atoms, giving graphite a theoretical capacity of 372 mAh/g.

Silicon anodes offer higher capacity (4200 mAh/g) but expand up to 300% during lithiation, causing mechanical stress and rapid degradation.

We encountered this expansion problem when developing prismatic batteries for power tools. Our initial silicon-graphite composite anode (15% silicon) showed 25% higher capacity than pure graphite but degraded to 70% capacity after only 200 cycles.

We sent samples back to our materials lab, where microscopy revealed anode cracking and delamination. The rework involved reducing silicon content to 5% and adding elastic polymer binders.

Testing equipment including charge-discharge cyclers, scanning electron microscopes, and impedance analyzers helped us optimize the formulation. The final version maintained 90% capacity after 800 cycles while providing 8% more energy than pure graphite anodes.

Electrolyte Composition and Ion Transport

The electrolyte serves as the medium for lithium ion movement between electrodes.

Most li ion battery systems use liquid electrolytes containing lithium salts (like LiPF6) dissolved in organic solvents. The electrolyte must conduct ions efficiently while remaining electrochemically stable across the battery’s voltage range (typically 2.5V to 4.2V).

Electrolyte decomposition causes capacity fade, gas generation, and safety risks.

Temperature affects electrolyte performance significantly.

At low temperatures below -20°C, electrolyte viscosity increases and ionic conductivity drops, reducing available power. At high temperatures above 60°C, electrolyte decomposition accelerates, forming solid deposits on electrode surfaces that block lithium ion access.

These solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) layers grow thicker over time, increasing internal resistance and reducing capacity.

| Electrolyte Property | Impact on Performance | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Conductivity | Determines charge/discharge rate capability | 8-12 mS/cm at 25°C |

| Voltage Stability Window | Limits maximum cell voltage | 0-4.5V vs Li/Li+ |

| Viscosity | Affects ion transport speed | 2-5 cP at 25°C |

| Thermal Stability | Influences operating temperature range | -40°C to 80°C |

| Lithium Salt Concentration | Balances conductivity and stability | 1.0-1.2 M |

During development of battery packs for light electric vehicles, we tested five different electrolyte formulations in our climate chambers. The standard formulation worked fine at room temperature but showed 40% capacity loss at -10°C.

We reformulated with low-viscosity solvents and additives that improve SEI formation. Testing involved 500 charge-discharge cycles at various temperatures, monitoring voltage, current, and temperature with data acquisition systems.

The optimized electrolyte maintained 85% capacity at -10°C and extended cycle life by 200 cycles at 45°C. This development took four months from initial formulation to production approval, including complete failure analysis when early samples generated gas during high-rate charging.

Need Expert Battery Chemistry Consultation?

Our engineering team can help you select the optimal electrode and electrolyte combination for your specific application requirements.

How Does Cell Design Affect Battery Performance?

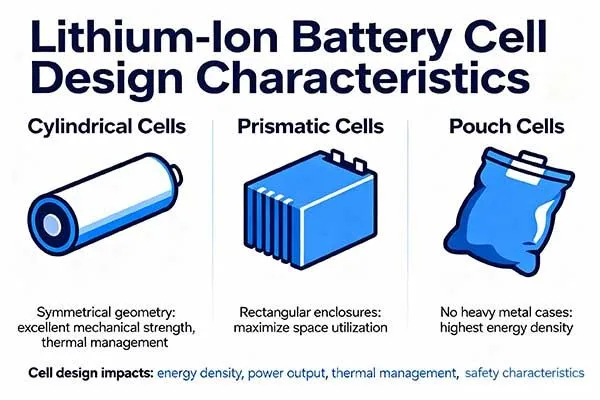

Cell design directly controls the energy density of lithium-ion batteries, power output, thermal management, and safety characteristics.

Cylindrical cells offer excellent mechanical strength and thermal management due to their symmetrical geometry. Prismatic cells maximize space utilization in rectangular enclosures. Pouch cells provide the highest energy density by eliminating heavy metal cases.

Each format suits different applications based on mechanical requirements, thermal conditions, and manufacturing capabilities.

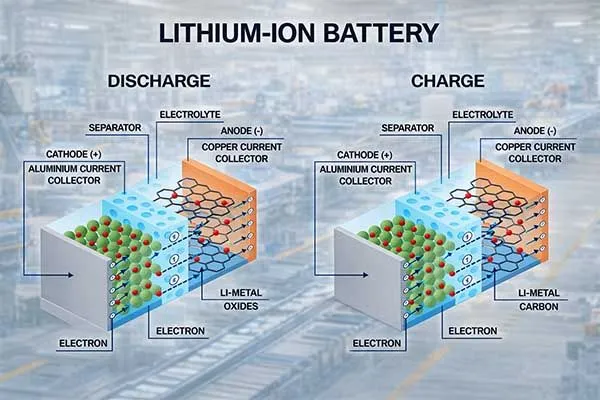

The physical arrangement of electrodes, current collectors, and separators determines how efficiently the battery converts chemical energy to electrical energy.

Design choices affect manufacturing cost, assembly complexity, and long-term reliability. Selecting the wrong format for your application leads to suboptimal performance and potential safety issues.

Cylindrical Cell Architecture and Advantages

Cylindrical lithium batteries use a jelly-roll construction where anode, separator, cathode, and separator layers wind around a central mandrel.

This design creates a mechanically robust structure that withstands vibration and mechanical shock. The cylindrical geometry allows efficient heat dissipation through the large surface area relative to volume.

Common formats include 18650 (18mm diameter, 65mm length) and 21700 (21mm diameter, 70mm length) cells.

The wound construction in cylindrical cells creates uniform pressure across the electrode layers, preventing delamination during cycling.

However, the geometry limits electrode area compared to prismatic or pouch formats of similar volume. This means cylindrical cells typically offer slightly lower energy density but better thermal performance and mechanical durability.

At our facility, we manufacture cylindrical cells for electric mobility applications using automated winding equipment. During a recent project for a European client requiring battery packs for e-scooters, we faced challenges with electrode alignment.

Initial samples showed capacity variation of ±5% between cells due to misalignment during winding. Our quality team identified the problem using X-ray inspection systems that revealed gaps in the electrode overlap.

We recalibrated the winding tension and added vision-guided alignment sensors. After implementing these changes, capacity variation dropped to ±1.5%, and the client placed an order for 50,000 cells.

This experience demonstrated how precise manufacturing control affects cell performance consistency.

Prismatic Cell Design and Applications

Prismatic lithium ion batteries stack alternating layers of anode, separator, and cathode in a rectangular metal case.

This stacked design allows efficient space utilization in rectangular battery packs, making prismatic cells popular for electric vehicles and large energy storage systems. The flat surfaces facilitate thermal management through direct cooling plates.

The main challenge with prismatic cells involves maintaining uniform pressure across the electrode stack. Uneven pressure causes current density variations, accelerating degradation in high-stress areas.

The metal case adds weight, reducing overall system energy density compared to pouch cells. Manufacturing complexity also increases due to the precise alignment required for multiple electrode layers.

We developed prismatic LFP cells for a stationary energy storage project where cycle life mattered more than energy density.

The client needed 6,000 cycle life at 80% depth of discharge. Our initial design achieved only 4,500 cycles before reaching 80% capacity retention. Investigation revealed that electrode edges experienced higher current density, causing accelerated degradation.

We redesigned the current collector tabs, distributing them across the electrode width rather than concentrating them at one edge. We also adjusted the electrode stack compression pressure from 0.3 MPa to 0.5 MPa using precision fixtures during assembly.

Testing this redesign on accelerated cycle life equipment running 24/7 took eight weeks. The improved design exceeded 6,500 cycles, and we delivered 10,000 cells for the client’s energy storage installation.

Pouch Cell Configuration and Trade-offs

Pouch cells eliminate the rigid metal case, using a flexible aluminum-plastic laminate instead. This construction minimizes inactive material weight, achieving the highest energy density among cell formats.

The flexible packaging allows various shapes and sizes, optimizing space utilization in battery pack designs. However, pouch cells require external mechanical support and show lower tolerance to mechanical abuse compared to cylindrical or prismatic formats.

Swelling presents a significant challenge with pouch cells. Gas generation during cycling causes the cell to expand, potentially damaging surrounding components or creating uneven pressure distribution within battery packs.

Proper pack design must accommodate swelling while maintaining compression to ensure good electrode contact.

| Cell Format | Energy Density (Wh/L) | Mechanical Strength | Thermal Management | Manufacturing Cost | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cylindrical | 450-650 | Excellent | Very Good | Moderate | Power tools, e-bikes, UAVs |

| Prismatic | 500-700 | Good | Good | High | Electric vehicles, ESS |

| Pouch | 550-750 | Fair | Fair | Low to Moderate | Portable electronics, drones |

| Cylindrical (21700) | 650-750 | Excellent | Excellent | Moderate | Electric mobility, RVs |

During development of battery packs for unmanned aerial vehicles, we tested both pouch and cylindrical configurations.

The client wanted maximum flight time in a compact form factor. Pouch cells offered 15% higher energy density, theoretically increasing flight time from 28 to 32 minutes. But vibration testing revealed that pouch cells degraded 30% faster under the mechanical stress typical of UAV operation.

We prepared custom test fixtures that simulated flight vibration profiles recorded from actual missions. After 100 hours of vibration testing combined with charge-discharge cycling, pouch cells showed visible delamination while cylindrical cells maintained integrity.

We recommended cylindrical cells despite the energy density penalty, and the final battery pack delivered 29 minutes of flight time with significantly longer service life. This case showed that paper specifications don’t always translate to real-world performance.

Looking for Custom Cell Design Solutions?

We can engineer cylindrical, prismatic, or pouch cells tailored to your mechanical, thermal, and energy requirements.

What Factors Determine Real-World Battery Lifespan?

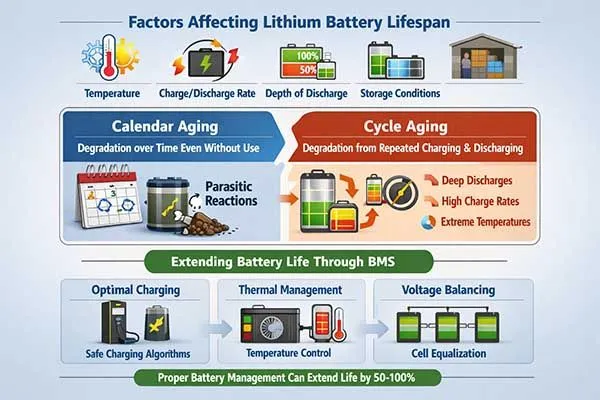

Real-world lithium battery lifespan depends on operating temperature, charge-discharge rates, depth of discharge, and storage conditions.

Calendar aging occurs even without use due to parasitic reactions at the electrode-electrolyte interface. Cycle aging accelerates with deep discharges, high charge rates, and operation at temperature extremes. Proper battery management systems can extend life by 50-100% through optimal charging algorithms, thermal management, and voltage balancing.

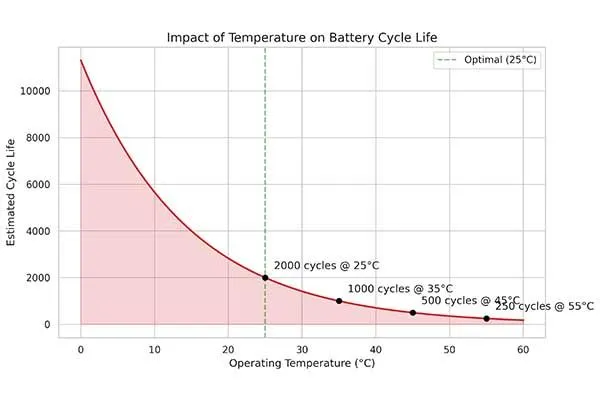

Most lithium ion batteries basics and applications show that cells degrade to 80% capacity after 500-2000 cycles depending on usage conditions.

Understanding degradation mechanisms helps you maximize battery investment returns and prevent premature failures.

Many applications fail to achieve expected battery life because operators don’t account for how usage patterns affect aging rates. The difference between laboratory cycle life and field performance often surprises users who don’t consider real-world operating conditions.

Temperature Effects on Battery Aging

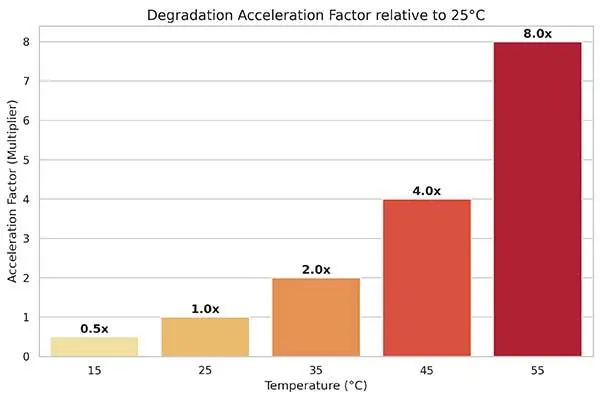

Temperature represents the single most important factor affecting battery lifespan. High temperatures accelerate chemical degradation reactions exponentially.

For every 10°C increase above room temperature, degradation rates roughly double. At 45°C, a battery that would last 2000 cycles at 25°C might survive only 1000 cycles.

Low temperatures below 0°C don’t cause permanent damage during storage but reduce available capacity and power during operation due to slower ion transport. Thermal management becomes critical in applications like electric vehicles and energy storage systems where batteries operate for extended periods.

Active cooling systems maintain optimal temperature ranges but add cost, weight, and complexity. Passive cooling through heat sinks and thermal interface materials works for lower power applications like power tools and recreational vehicles.

We learned this lesson when developing battery packs for outdoor energy storage in hot climates. A client in the Middle East reported capacity fade to 70% after only 400 cycles, far below our 1500 cycle specification.

We retrieved failed samples and analyzed them at our testing facility. Microscopy showed severe electrode cracking and thick SEI layer formation characteristic of high-temperature operation. When we checked the installation, we found the battery enclosure reached 55°C during summer afternoons because the client installed it in direct sunlight without ventilation.

We redesigned the battery management system to reduce maximum charge voltage at high temperatures and recommended adding ventilation fans to the enclosure. We also adjusted our cell chemistry, using electrolyte additives that form more stable SEI layers at elevated temperatures.

After these changes, the replacement system achieved 1200 cycles before reaching 80% capacity. This experience cost us significant warranty replacements but taught us to account for worst-case environmental conditions during design.

Charge Rate and Depth of Discharge Impact

Fast charging convenience comes with degradation penalties. Charging at rates above 1C (where 1C means charging from empty to full in one hour) causes lithium plating on the anode surface, especially at low temperatures.

This plating permanently reduces capacity and can create safety hazards if dendrites grow through the separator. Discharging at high rates generates heat and causes voltage drops that stress the cell chemistry.

Depth of discharge (DOD) also significantly affects cycle life. Shallow cycling between 30% and 70% state of charge extends life dramatically compared to full 0-100% cycles. Many successful battery installations limit DOD to 80% even though this sacrifices usable energy capacity.

The trade-off between usable energy and cycle life depends on application economics and replacement costs.

Tips:

Real-world performance is closely tied to sustainability. Batteries that maintain stable capacity over longer lifecycles reduce replacement frequency, lower total material consumption, and contribute to more sustainable energy storage systems across industrial applications.

Battery Management System Optimization

Modern battery management systems (BMS) do much more than prevent overcharge and overdischarge. Advanced algorithms balance cell voltages, estimate state of charge and state of health, and implement charging strategies that minimize degradation.

Temperature-compensated charging adjusts voltage limits based on cell temperature. Adaptive algorithms learn individual cell characteristics and adjust balancing to maximize pack capacity.

During development of lithium ion battery packs for light electric vehicles, we tested different charging strategies using our cycle life testing equipment. Standard constant-current constant-voltage (CC-CV) charging to 4.2V achieved 800 cycles to 80% capacity.

We implemented a multi-stage charging algorithm that reduced final voltage to 4.1V and added a brief rest period mid-charge to allow lithium ion redistribution within electrodes. This algorithm extended cycle life to 1100 cycles with only 5% reduction in usable energy.

We also added temperature-based derating that reduced charge current above 40°C. Field testing over 18 months with 50 prototype vehicles confirmed the laboratory results. Based on this data, we now recommend this charging strategy for all light electric vehicle applications.

Developing and validating this algorithm required extensive testing using thermal chambers, battery cyclers, and real-world driving profiles, but the improved customer satisfaction and reduced warranty costs justified the investment.

| Degradation Factor | Effect on Cycle Life | Mitigation Strategy | Implementation Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Temperature (>40°C) | 40-60% reduction | Active or passive cooling | Medium to High |

| Low Temperature (<0°C) | 20-30% reduction during use | Pre-heating before charge | Low to Medium |

| Fast Charging (>1C) | 30-50% reduction | Temperature-compensated charge limiting | Low |

| Deep Discharge (>90% DOD) | 40-60% reduction | Limit usable DOD to 80% | None (software only) |

| High Voltage (>4.2V) | 50-70% reduction | Reduce maximum charge voltage | None (software only) |

| Poor Cell Balancing | 20-40% reduction | Active balancing BMS | Medium |

Storage Conditions and Calendar Aging

Batteries age even when not in use.

Calendar aging occurs due to slow parasitic reactions at electrode surfaces that consume lithium ions and increase internal resistance. Storage at high temperatures or high state of charge accelerates calendar aging. The optimal storage condition for lithium polymer batteries and li-ion battery types involves 40-60% state of charge at cool temperatures around 15°C.

Many applications involve intermittent use with long storage periods between operations. Recreational vehicles, backup power systems, and seasonal equipment might sit unused for months.

Without proper storage preparation, batteries can lose significant capacity or even become unrecoverable. Good storage practices include periodic partial cycling to redistribute lithium, maintaining moderate state of charge, and avoiding temperature extremes.

As a lithium ion battery manufacturer, we help customers develop storage protocols.

One client with seasonal recreational vehicle demand asked how to maintain batteries during six-month off-season periods. We conducted accelerated aging tests comparing different storage conditions.

Cells stored at 100% charge and 25°C lost 15% capacity over six months. Cells stored at 50% charge and 15°C lost only 3% capacity. Based on these results, we recommended customers charge batteries to 50% before storage and provide a small maintenance charger that tops up monthly to compensate for self-discharge.

We also created a storage mode in the BMS that prevents full charging during maintenance cycles. These simple procedures extended off-season storage life from 3 years to over 7 years in field testing.

The testing program involved climate chambers maintaining precise temperature control and automated data logging over 18 months to validate our recommendations.

Maximize Your Battery Investment ROI

Our battery management solutions and usage protocols can double your battery system lifespan while maintaining performance.

Conclusion

Understanding how lithium ion batteries work requires knowledge of chemistry, cell design, and real-world operating conditions.

The electrochemical reactions that power these devices involve lithium ion movement between carefully engineered electrode materials through electrolyte solutions. Cell format selection between cylindrical, prismatic, and pouch designs depends on application requirements for energy density, mechanical strength, and thermal performance.

Real-world lifespan depends critically on operating temperature, charge rates, depth of discharge, and storage conditions. Advanced battery management systems can significantly extend life through optimized charging algorithms and thermal management.

The energy density of lithium-ion batteries continues improving through materials innovation and design optimization, enabling new applications across electric mobility, energy storage, power tools, and aerospace.

Successful battery implementation requires matching cell chemistry and format to application demands while accounting for environmental conditions and usage patterns that affect degradation rates.

Frequently Asked Questions

Click to explore more information about Lithium ion Batteries

Q: What is a lithium-ion battery?

A: A lithium-ion battery is a rechargeable energy storage device that uses lithium ions moving between the anode and cathode to store and release electrical energy. It is widely used in electronics, electric vehicles, and energy storage systems due to its high energy density and long cycle life.

Q: What is the biggest problem with lithium batteries?

A: The biggest problem with lithium batteries is thermal runaway, which can occur due to overcharging, short circuits, physical damage, or manufacturing defects, potentially leading to overheating, fire, or explosion if not properly managed.

Q: What not to do with lithium-ion batteries?

A: Lithium-ion batteries should not be overcharged, deeply discharged, punctured, crushed, exposed to high temperatures, or charged with incompatible chargers, as these actions can reduce battery life and create safety risks.

Q: What are the disadvantages of a lithium-ion battery?

A: The main disadvantages of lithium-ion batteries include higher cost compared to some alternatives, sensitivity to high temperatures, gradual capacity degradation over time, and the need for battery management systems to ensure safe operation.

Q: Can I charge a Li-ion battery with a regular charger?

A: No, lithium-ion batteries should only be charged with chargers specifically designed for Li-ion chemistry, as regular chargers may not control voltage and current accurately, increasing the risk of overheating or permanent battery damage.

Q: How are lithium-ion batteries made?

A: Lithium-ion batteries are made by producing electrode materials, coating them onto metal foils, assembling cells with separators and electrolyte, sealing the cell, and performing formation and aging processes to ensure performance, safety, and reliability.